On-line modulation of conitive control level

(Blandyna Żurawska vel Grajewska)

Congruency effect

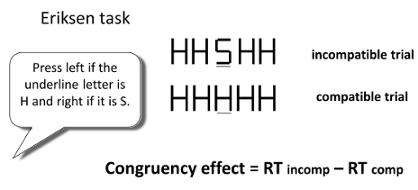

When we perform an intended action toward a target object, for instance

we name the shape of it like in the Eriksen’s task, the irrelevant accompanying

objects can either support that action (when are associated with the same

response = congruent trial) or interfere with it (on incongruent trials, where the

target and flanking objects are associated with alternative responses). This

difference between performance on congruent and incongruent trials is called ‘a

congruency effect’ or simply

‘interference’ (Eriksen &

Eriksen, 1974).

|

Dynamic changes of conitive control level

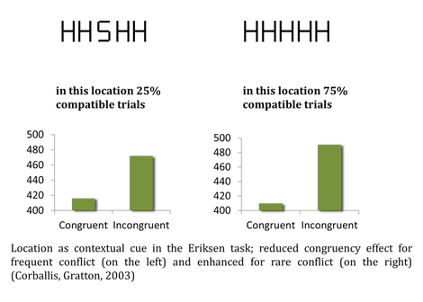

Interference is larger when conflict is unexpected (for instance occurs rarely in the block) (Gratton et al 1992). Recently it was shown that such modulation of the interference size can be more sophisticated. Even if there is an equal percent of congruent/incongruent trials in the block, the interference can be larger for the one part of trials (distinguished by salient stimuli feature e.g. certain location, colour or shape) where the conflict is rare and smaller for the other part with more frequent conflict (distinguished by opposite value of stimuli feature). Such a pattern of result is called ‘the context-specific proportion congruent effect’ (CSPC): a congruency effect size differentiated according to different congruent-to-incongruent trials ratios assigned to stimuli feature within one block.

|

Effective and ineffective contextual cues

When are such dynamic, on-line changes in the cognitive control level possible? Some stimulation dimensions used as contextual cue, i.e. feature distinguishing parts of trials with different frequency of conflict, were effective (CSPC observed), while others failed. The cue relevancy for the particular task was suggested as critical

(Corballis & Gratton 2003; Crump, Vaquerro & Milliken, 2008; Żurawska vel Grajewska, Sim, Hönig, Herrnberger & Kiefer, 2012), although some conflicting data were observed too (Vietze & Wendt, 2009). The aim of our research is to examine necessary conditions for effective contextual cue also for other modality and types of tasks with conflict.

References:

- Corballis, P. M. & Gratton, G. (2003). Independent control of processing strategies for different locations in the visual field. Biological Psychology, 64, 191-209.

- Crump, M. J. C., Vaquerro, J. M. & Milliken, B. (2008). Context-specific learning and control: the roles of awareness, task relevance, and relative salience. Consciousness and Cognition, 17, 22-36.

- Eriksen, B. A. & Eriksen, C. W. (1974). Effects of noise letters upon the identification of a target letter in a nonsearch task. Perception & Psychophysics, 14, 155-160.

- Gratton, E., Coles, M. G. H. & Donchin, E. (1992). Optimizing of the use of information: Strategic control of activation of responses. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 121, 480-506.

- Jacoby, L. L., Lindsay, D. S. & Hessels, S. (2003). Item-specific control of automatic processes: Stroop process dissociations. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 10, 638-644.

- Vietze, I. & Wendt, M. (2009). Context specifity

of conflict frequency-dependent control. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental

Psychology, 62, 1391-1400.

- Żurawska vel

Grajewska, B., Sim, E.-J., Hönig, K., Herrnberger, B. & Kiefer, M. (2011).

Mechanisms underlying flexible adaptation of cognitive control: Behavioral and

neuroimaging evidence in a flanker task.

Brain Research, Vol

1421, 52-65.